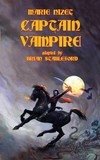

Captain Vampire

by Marie Nizet

adapted by Brian Stableford

All Cossacks are thick-skinned, it's true, but Boris Liatoukine plied the knout so often and hard that one day, when he found himself in an out-of-the way spot with his men, they stripped him naked, intending to freeze him to death!

Water cascaded down on him, and when he had the appearance of a pretty crystal statue, the Cossacks, glad to be rid of their Lieutenant, got back on their horses. When they arrived back at camp, the first person they saw was Liatoukine, fully dressed and not even chilly. One of the Cossacks went mad, and Liatoukine had the rest executed by a firing-squad. Ever since then, he's been known as Captain Vampire...

Written in 1879 (18 years before Dracula) by 19-year-old Marie Nizet, Captain Vampire, in its method and tone alike, is way ahead of its time. Although its plot has supernatural elements, and its antagonist is manifestly demonic, the novel's true purpose is to bring out the horror of war. A significant work in the history of horror fiction, it is undoubtedly one of the finest literary works ever to have made use of the vampire motif.

Translated and annotated by Brian Stableford.

Contents:

Captaine Vampire (1879) by Marie Nizet; Introduction, Afterword and Notes by Brian Stableford.

Read the reviews...

Clearly – as the blurb tells us – this is primarily a book that sets to relay the horror of war. Indeed, Stableford points out that this was, at the time, an almost unheard of form and certainly the fact that a nineteen-years-old young woman wrote this makes the story remarkable. Unlike other stories we have looked at from this general period the book does not carry Gothic trappings and is a prime example of the vampire as allegorical figure.

The folklore is sparse but there is a small amount there. Liatoukine is cadaverous in appearance, tall and thin he casts a huge, spreading shadow but what I found remarkable was the description of his eyes: “The eyes, which seemed the only living things in that impassive face, displayed a singular feature: each eyeball, iridescent as a topaz, had a vertically slit pupil, such as one observes in animals of the feline family.” I liked this feline association.

He is able to mesmerise with his eyes and, it is suggested later, kill by holding a victim in said trance. He is drawn as a villainous, evil character – and there is certainly some pro-Romanian politicising in that – but he is certainly at home in daylight. There is some suggestion that he can be in two places at once and seems to have a habit of killing his wives. We hear of two dead wives prior to the novel and a third in the coda. It is suggested they are strangled but this is not all for we are told with regards the first two, “the two women had been strangled and that they both bore a little red mark on the neck – the vampire’s teeth, you know…” His habitual loss of spouse reminded me very much of the ambitions of Varney the Vampire and, to a degree, the ending of Polidori’s The Vampyre.

All in all, this book further expands the vista of the pre-Stoker vampire.

Taliesin